Although the coronavirus currently dominates the news, and has done so for several months, there are a dearth of images for death by the virus. The reasons are threefold: The process of death is quick (two weeks to two months); the level of contagion is high, as a respiratory disease, the virus is so communicable that visitors, including family, are prohibited, and those who die, do so alone. There are no distinctive, visible signs of having developed COVID-19 until the sick are gravely ill.

A condition that lacks an image gives the illusion that the condition does not exist. Without visual evidence of the fact, the fact can be denied. The abysmal government response was due not to the novelty of the pandemic, but to an economic focus on making the wealthiest individuals wealthier and in not addressing a health crisis affecting the many. The government’s incompetence was not an accident, but rather a systematic practice of: protecting the wealthy and exploiting the poor.

Representative images of an illness create a profile in which symptoms set off an alarm and also, by default, act as a stigma. Because there are no clear, visible signs of the Coronavirus infection, there is no profile of the carrier and therefore, no representation of those dying from the disease. With AIDS, the stigma didn´t occur by default but was consciously fabricated. In AIDS the image of a family huddled around a loved one with Kaposi sarcoma was not uncommon. The intention was to stigmatize the person with AIDS as the deviant. Without representative images, COVID-19 stigmatizes the virus, not the person who contracts it. With no images of the dying, there are no visible symptoms and no stigma. This is not an innocent choice.

The lack of representation is intended to convey the universality of the Coronavirus, that it affects us all equally. This is false. Potentially, anyone can contract the disease, but in reality, circumstance dictates your chances of contagion and death. It is important to understand the difference between probable and potential; the wealthy have the potential to die of the Coronavirus, but the poor have a probability of dying from the disease. The expression, We are all in the same boat is frequently used to suggest the egalitarianism of the disease, but a closer look at those most affected by the virus, easily shows that we are all not in the same boat; some of us are in yachts and some are struggling to stay afloat on overcrowded rafts. I witnessed people standing in line for hours to get a bottle of milk, but five minutes away, in the highly gentrified neighborhood of SOHO, the wealthy residents have vanished. The lie is to pass the potential off as a certainty.

The mortality rate among those less entitled in the making of decisions is much higher. Not just in matters of health and access to medical care, but In everyday decisions like choosing to take the subway or avoiding unnecessary exposure to the virus by not taking the subway. If you live in the Bronx, don´t have a car and must travel to a job you must keep in order to live, you have no choice; you must take the subway. Also among those with limited powers of choice are older people in senior residencies, the handicapped, the mentally ill and simply “the poor.”

But who are the poor? The world is divided among the rich and poor, but when it comes to poverty, a race component overrides the EDP ( Economic Death Probability). According to the American Public Media (APM) Research Lab studies, the mortality rate from Covid-19 among African Americans is 2.4 times higher than it is for Caucasions. The color of coronavirus: COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity in the U.S. states that “While we have an incomplete picture of the toll of COVID-19, the existing data reveals deep inequities by race, most dramatically for Black Americans”[1] In the absence of images, journalists have been trying to make us “see” the inequity in COVID-19 mortalities through their writing. The word “color” in the title of the article is a substitution for the skin colors of the dead in the pictures we do not see.

Do Blacks die because they are black or because they are poor?

a) Being a person of color, your essence dictates your existence, makes you poor.

b) A higher percentage of Blacks and Latinos are poor; poverty makes you die.

In photographs of the deceased, the technical sophistication of the photo, lighting, color, setting, the arrangement of the subject, whether they are alone, in a bed, the bedding, furniture, how the subject’s hair is arranged, how they’re dressed may offer data about the economic status of the dead person, but in another way, death is the great equalizer. What a photograph is able to do more accurately is to identify ethnicity and race. This visual evidence, seeing the skin, bodies and faces of those who died from COVID-19 would have created an icon of racial disparity in the US. Not having images of the dead makes the evidence invisible: death from COVID-19 in the U.S. is brown and black.

Comparison COVID-19 / AIDS

If we compare COVID-19 with AIDS, the later disease had no clear racial/class divide (other than sex workers who usualy fall below the poverty line). AIDS was associated with the stereotypically conventional (heterosexuals) versus the non-conventional (promiscuous gay men), purity versus pleasure. Death by AIDS was viewed as a moral dilemma. The same is not true In the age of the Coronavirus. In this pandemic, the wealthy withdraw to summer homes or remain in doorman buildings getting deliveries. If they stay in the city, they have the choice not to use public transportation (assuming they used it in “normal” times). The poor must use subways and buses to get to their jobs as home attendants, MTA drivers, grocery clerks and package delivery persons. While the wealthy can afford to live for an extended period without a paycheck, the poor cannot. They must stand in lines in grocery stores and shelters in smaller, possibly overcrowded homes, in buildings without access to virtual living via the internet. From yoga classes to schooling, university classes, doctors appointments, etc., life is now lived on a screen, and those who don’t have a smartphone, computer, internet access or simply lack space or privacy, have no lives.

The poor die. Why? Because they have no access to the way life goes on now: on a screen. They don’t research the pandemic because they don’t have the capability to do so. And they can no longer gather information through the community, now isolated, as they once did. It is shocking how inequality relates to death in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The mortality profile is not neutral but the image of death by Coronavirus is neutral by default, because we have no image. Unlike the tragic representations of families or loved ones visiting the gaunt AIDS patient in his final days, there are no images of visitors in the case of the Coronavirus. The process of death is quick, and the upward trend in the number of cases also moves with shocking speed. Death comes quickly, but a photograph may be taken in an instant. Yet we see no images of living with the Coronavirus or of dying from it. The primary image of the illness is the representation of the virus itself, a sphere covered with red squid-like protrusions. Photos of people dealing with COVID-19 would show evidence of hospitals unprepared for a pandemic and rooms with patients dying alone. Death by the Coronavirus is not a pretty death. A high percentage of the mortally ill are elderly and in bad shape and the places where they die are disorganized disaster areas. If the virus is airborne, does the contagion die with the breath? How long does the virus remain in and on the host after death? A refrigerated truck is parked in front of a funeral home in the East Village across the street from the Anthology Film Archives. This container of dead bodies is visible to all but ignored and unrepresented by any image I have seen. There are no in funerals at present, no viewings for the bereaved. There is no space for the dead and none for their deaths.

Death by Coronavirus is neutral. A carrier may look normal one day and be dead the next. There are no signs of sickness beyond death itself. But what is not neutral is the way death is handled, with no way to take care of the dying, and no space for the dead.

A collage of the dead on the front page of the New York Times

After the pandemic was seriously embedded in New York in early April, over the next two months, there were no more commentaries on the lack of prevention or on the negligence of the government. The news covered current events, a daunting task in itself. The newsletter from local officials focused on where to find free food distribution, how to apply for grants, procure funding tips and programs to elevate the spirit, including online concerts, readings and dance lessons and later, as tests became available, where to get tested and other local sources.

These were important resources in a time of survival mode, but it was also petty stuff when seen next to the fast rising contagion and death toll of the Coronovarius. Pettiness is a way to to move focus away from what is behind the exponential growth of the pandemic: a negligent government. Facing a crisis of this immensity, it’s easier to deal with the day-to-day aspects of survival, rather than the broader questions of the cause and effect of the crisis.This duality is also political and a way to divide people into two types: aware or passive.

It is only recently, after May 15th, when New York was scheduled to reopen, and when the number of cases had gone down, and the national death count was approaching100.000, that Americans went in two directions. One direction was, I’m alive, many died, but we didn´t, so let’s get together, go out, have fun and return to life without restrictions. The other direction was, This is a moment to breathe, and the first breath must be used to demand accountability from those at blame, because although I’m alive, many are not.

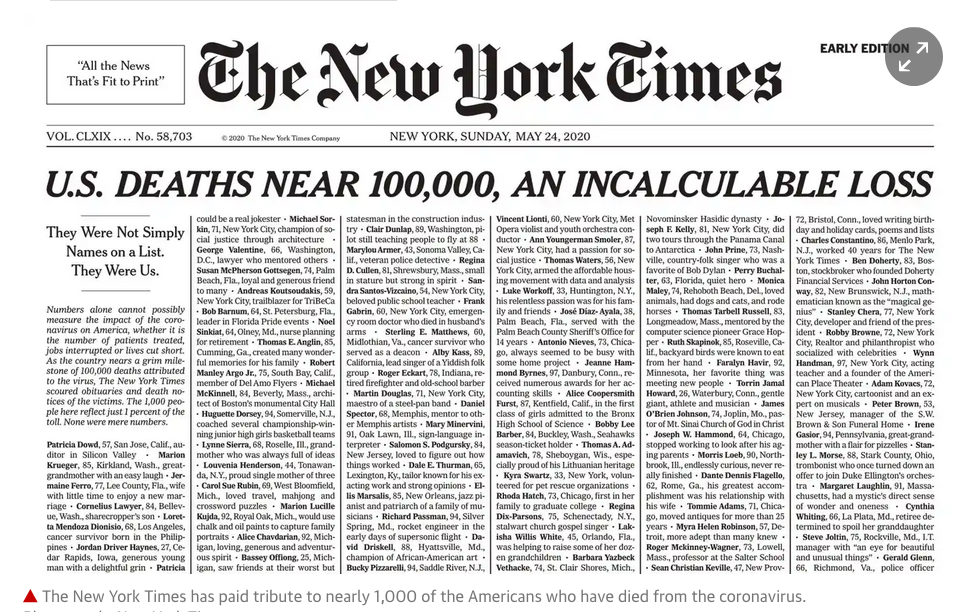

This second approach is what is explicit in: The Project Behind a Front Page Full of Names A presentation of obituaries and death notices from newspapers around the country tries to frame incalculable loss by By John Grippe on May 23, 2020[2].

The origin of the front page presentation was explained in a Times Insider piece. “Simone Landon, assistant editor of the Graphics desk, wanted to represent the number in a way that conveyed both the vastness and the variety of lives lost….Ms. Landon…came up with the idea of compiling obituaries and death notices of COVID-19 victims from newspapers large and small across the country, and culling vivid passages from them.”

A person may be identified by LANGUAGE (name), IMAGE (photograph) and NUMBER ( ID, DNI, or SS). In an effort to identify the person as human beyond quantity (statistics), the New York Times listed the names, ages and some personal information of Americans who died from COVID-19 on its front page. A name is not a code. It has no meaning other than emotional value for those who know the person. A photograph, even when taken for an objective purpose such as a passport photo or a driver’s license, contains many elements. A photograph gives not only statistical information: gender, race and age, but also personal information through facial expression, quality of the skin, hair, etc.. One receives a lot of information from an image, not only values but emotions (such as the level of bitterness, pain, discomfort or despair I witnessed over the two month process of my father dying).

To list names with a defining comment simply moves obituaries to the front page. The news is death displayed as art.

Simone Landon, assistant editor of the Times Graphics desk, described the list of nearly a thousand names from hundreds of newspapers printed on the front page, as a “rich tapestry... A team of editors from across the newsroom, in addition to three graduate student journalists, read them and gleaned phrases that depicted the uniqueness of each life lost:

‘Alan Lund, 81, Washington, conductor with ‘the most amazing ear’ … ‘

‘Theresa Elloie, 63, New Orleans, renowned for her business making detailed pins and corsages … ‘

‘Florencio Almazo Morán, 65, New York City, one-man army … ‘

‘Coby Adolph, 44, Chicago, entrepreneur and adventurer … ‘“[3]

The danger of the war metaphor

The front page was printed on the first day of the Memorial Day weekend. Memorial Day commemorates those who lost their lives in service to their country. The word “war” has been used as a metaphor for the pandemic. This is a war we are fighting. Cynthia Enloe, in her text COVID-19, “Waging War” Against a Virus is NOT What We Need to Be Doing” (March 23, 2020) argues, as the title makes explicit, that the metaphor of war is the wrong one. “To mobilize society today to provide effective, inclusive, fair and sustainable public health, we need …. to resist the seductive allure of rose-tinted militarization.[4]”

There is another reason to stop using the metaphor of the war for a disease: death is taken for granted, and read as the default ending. The Commentary on the web site “War on The Rocks” by Mark Hannah April 17, 2020, “Stop Declaring War on a Virus” reads, “Brett Crozier, the recently fired captain of the USS Theodore Roosevelt, broke the chain of command when he wrote a letter proposing a quarantine of more than 100 Coronavirus-infected sailors during a stop in Guam. He acknowledged that immobilizing a “deployed U.S. nuclear aircraft carrier … may seem like an extraordinary measure,” but reasoned, “We are not at war. Sailors do not need to die.” [5]“

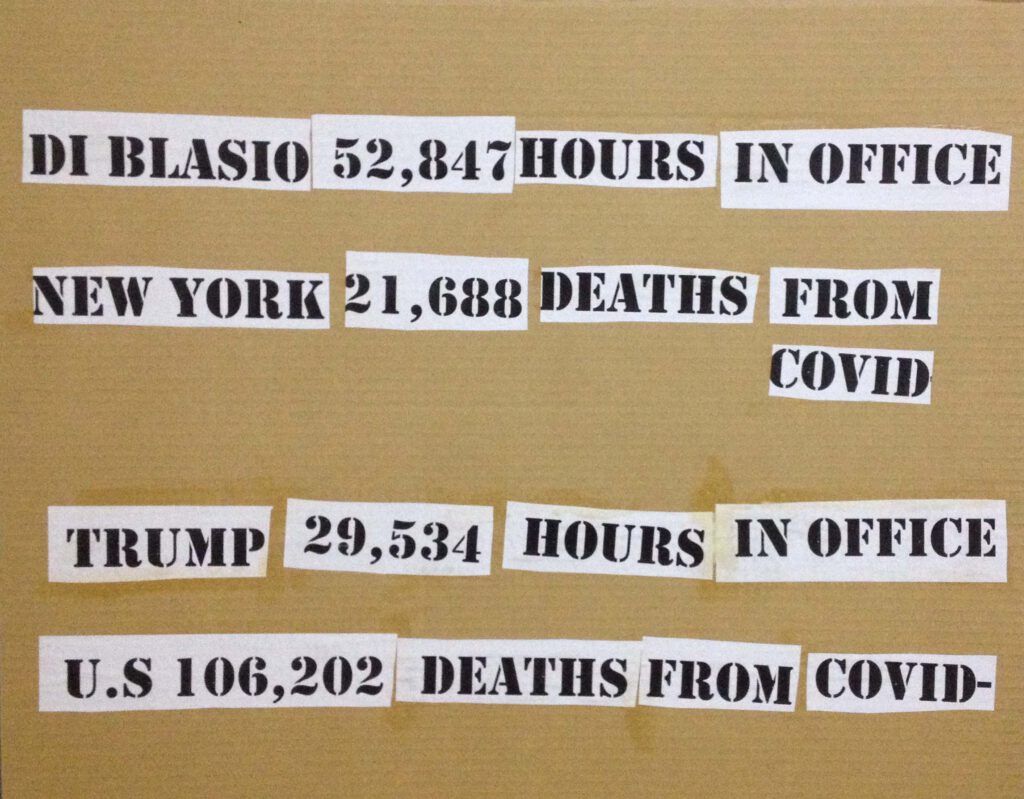

The idea that “we are not at war, and we do not need to die”, is a way to say that the responsibilities that the State has with the individuals are not exempted in the face of a pandemic. When the government uses a metaphor of war for the Coronavirus, they justify their wrong doing. Did 100.000 people die in combat with the virus? Or from the years of negligence by this government?

Government Negligence

Negligence is a consequence of lack of action; the failure to do something; the default. Negligence is the opposite of activism, which does; negligence does not do or undoes. The Obama administration created a playbook to respond to an outbreak of a “novel Coronavirus.” According to by Ryan Goodman and Danielle Schulkin from justsecurity.org in the article “Timeline of the Coronavirus Pandemic and U.S. Response”, “…the timeline is clear: Like previous administrations, the Trump administration knew for years that a pandemic of this gravity was possible and imminently plausible. Several Trump administration officials raised strong concerns prior to the emergence of COVID-19 and raised alarms once the virus appeared within the United States. While some measures were put in place to prepare the United States for pandemic readiness, many more were dismantled since 2017.”[6]

The article, written on April 13, 2020 and edited May 7, 2020, outlines the facts. It is a timeline of the government failures. Among them:, stopping exercises to prepare for a pandemic and cutting funds for that program, incomplete production of a prototype for the N95 mask and failure to acquire adequate amounts of PPE (personal protection equipment) and ventilators, cutting funds in public health and in research programs, including a study on the mutation of viruses from animals to humans, turning a deaf ear to the warnings of experts, firing advisors, cutting budgets in health, dismissing threat assessments, ignoring warnings included in an underprepared report and ignoring warnings once the pandemic was a reality.

In the United States, famous for courtroom disputes in cases of negligence, there is no response to federal negligence by those in power. Absence of accountability at the top tiers of power justify social revolution.

Comparing widespread demonstrations/riots in reaction to the George Floyd murder, with non-reaction to the governmental negligence which helped create a pandemic

I am writing this on May 30th, 2020, with the deafening sounds of helicopters overhead and rioting on the streets below. The riots, in reaction to the murder of George Floyd, make sense. But where is the revolt against a negligence that allowed a virus to become a pandemic? Why do people have less problem accepting negligence than direct wrongdoing? Negligence is systematic, not something that happens by mistake. Negligence is the civilized version of genocide.

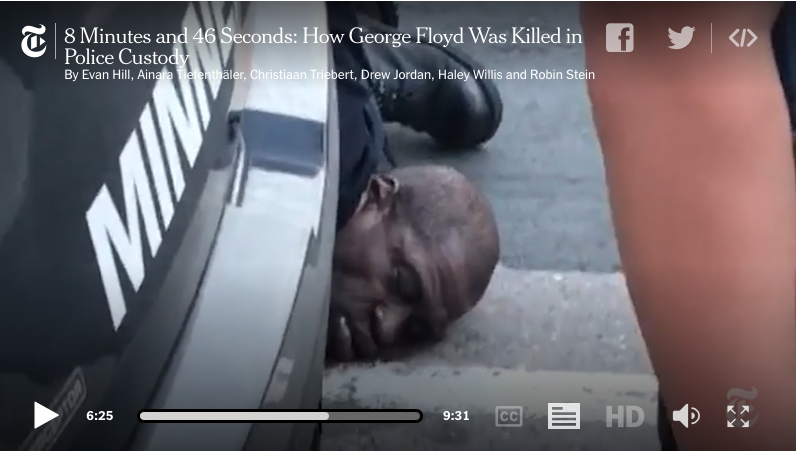

Governmental negligence is invisible both in the way it is acted out and in its effect: 100,000 unphotographed dead Americans. People are rioting because a video of George Floyd being murdered was made public.

A riot needs an image. In her opinion piece in the New York Times, “Where are the photos of people dying of Covid?,”[7] Sarah Elizabeth Lewis states, “In times of crisis, stark images of sacrifice or consequence have often moved masses to act.” The piece is Illustrated with images of cardboard box coffins at the Gerard J. Neufeld funeral home in Flushing, Queens. The coffins are marked “HEAD,” at one end.

We need images of those who died to stop government negligence, systematic abuse and “the excess of capitalism.” But we don’t have them. The excuse for having no images of the dead or the dying is medical privacy. We have not seen how the virus affects the expression of its host or how the body tissue is destroyed. When my father died three years ago, I saw the effects of death by Cancer. My father’s legs were swollen and yellowed like old marble, his face was purple and his arms so atrophied he was unable to hold a cup. We were never particularly close, but his decline had a profound effect on me. The difference between seeing and not seeing is important. Personalized death in a terrifying, visceral way made me fear death. Would unseen images of the mortally ill, make an equally profound impression on those of us grappling with this “invisible” enemy?

Images of dying serve as a warning of death. The Florida man dressed as the grim reaper in the beach to warn people of the consequences of returning to the “old normal” in a time of COVID-19. Death is usually a private matter, but in a pandemic, images of death are a public necessity, and we should see them.

The image of the dead

Images have been used to memorialize those who died from COVID-19. For their “We Remember” project,CNN [8] states that “More than 100,000 people in the US have died from Covid-19. Here, 105 families share their favorite memories of those they’ve lost. If you have someone you’d like to honor, submit their story.” The accompanying quotes from family or friends under a photo of the deceased are touching and represent a valid way to honor their loved ones, but images taken from life are not a substitute for images of the dead and the dying. To remember a loved one at his or her best, as we are told to do,can also be a way to erase the reality of their deaths.

When I was 26 the person I loved the most in the world, hanged himself after taking pills. He left me a note that I took to the police to get access to his last picture. The police didn’t want to show me the picture they’d taken when they found him. “You are not going to like it,” they said, “you should remember him the way he was when he was alive.” “I want to see the picture,” i insisted, “And I want a copy.” The policeman wouldn’t give me a copy, but he did show me the picture. Twenty six years later I have a vacation photo to remind me of him as he was, but the picture most ingrained in my brain, as it should be, is the police photo of him hanging; that image has changed the way I am.

These images we see pay tribute to life, but our demand for justice means we must pay tribute to death. The tribute-to-life images do not represent the reality of suffering nor the racial or economic reality of the dead. That is not their purpose. We need images that show the same stark reality we see in the videoed death of George Floyd. We need to see the effect of the Coronavirus on the human body and the actual deaths of real human beings.

The image of the policeman kneeling on the neck of George Floyd is so clearly wrong that it transforms his powerlessness in death into racial strength. Being black, your essence, dictates your existence; makes you poor and then you die. Being black makes you powerless and then you die. Powerless against the pandemic or the police. In the video, made available with the online New York Times article, “8 minutes and 46 seconds: How George Floyd was Killed in Police Custody”[9] offers an image of death. You see Mr. Floyd begging for breath, the pain in his eyes, his agony, his eyes rolling back, his mouth open, the blood then his inert body, still with a knee at the neck. We need an image of COVID-19 that depicts the deaths and the loss, to make us understand the dimension of negligence.

The establishment of the Black Lives Matter movement (2013) differs from the massive reaction to the murder of George Floyd. In the later, people are not proclaiming a fact but confronting a threat. If the spread of the coronavirus affects African Americans more than Caucasions, Africans Americans in the street, in an act of civil disobedience, also represent the threat of death with their presence. Black protesters in large numbers, dismissing social distancing are using their bodies as a lethal weapon. If by being black I have a greater chance to die, you, who have created the opportunity for my increased mortality rate, are going to die, too. And this time, I am not dying alone and with no images of my death. There have been no images of black COVID-19 deaths in the news, although it has been documented that blacks die at twice the rate of whites. By going to the streets in protest, I give the world an image of me being alive, before you, a federal agent or a negligent president, kill me and put my body in a plastic bag or a cardboard box. Protests offer an image of vitality to contrast the lack of images of death.

The protests by and for African Americans happening right now in the United States are not only protests of liberation for a race, but protests and a liberation movement for all who are powerless. And powerless, in the current state, with the current government, is what we all are.

June 1st 2020 1am

________

On June 1st, a few hours after I’d finished writing this essay, protests in front of the White House compelled the president to confine himself and his family in a basement bunker. For years, he has exhibited a disregard for the lives of others and caused untold deaths of Americans through his default amorality. Now, protestors dictated his life, at least for a few hours. Things are not going fine in this country. The pandemic is not under control, and drinking bleach does not stop the coronavirus. Trump’s constant media presence meant to turn his persona of stupidity into one of competence, is no longer plausible. He got the message. Now we are all, including the president, in a lock down. He should step down, the country is calling for it!

June 2nd 2020

Edited by Keith McDermott

[1] https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/23/reader-center/coronavirus-new-york-times-front-page.html

[3]https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/23/reader-center/coronavirus-new-york-times-front-page.html

[4] https://www.wilpf.org/covid-19-waging-war-against-a-virus-is-not-what-we-need-to-be-doing/

[5] https://warontherocks.com/2020/04/stop-declaring-war-on-a-virus/

[6] https://www.justsecurity.org/69650/timeline-of-the-coronavirus-pandemic-and-u-s-response/

[7] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/01/opinion/coronavirus-photography.html?auth=login-email&login=email

[8] https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2020/health/coronavirus-victims-memories/

[9]https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/31/us/george-floyd-investigation.html?action=click&block=associated_collection_recirc&impression_id=313834974&index=0&pgtype=Article®ion=footer By Evan Hill, Ainara Tiefenthäler, Christiaan Triebert, Drew Jordan, Haley Willis and Robin Stei Published May 31, 2020